Buried beneath Titahi Bay, is a series of silt and peat beds, around 10m thick that contain subfossil tree stumps that have grown 'in-situ' which represent a former forest.

The peat and silt beds are covered over by rust-stained sands and well-rounded gravels. It is thought that the stumps are mostly rimu, but matai and totara pollen has also been identified in the associated sediments. Radiocarbon dating indicates the wood is over 35,000 years old and probably dates from the last warm Interglacial Period that lasted from 120,000 to 80,000 years ago.

Subfossil tree stumps are not a common occurrence anywhere in the world and the Wellington region is fortunate to have two localities where they can be observed; the other site being at the Kaiwhata River mouth on the Wairarapa coast. They are known as subfossil because they are preserved but haven't been turned into stone.

In the past, during the colder glacial periods, forests in the Wellington region were forced down from higher elevations as the snow line dropped, to lowland and coastal areas where the climate was more suitable for tree growth. At the same time, sea levels dropped as water became locked up in ice sheets. During this time, the Porirua shoreline was several kilometres westward of its current position. Titahi Bay was part of a low-lying valley and Mana Island was connected to the mainland. Part of this geology remains just under the water and is known as 'The Bridge'; an area of shallow water 4-9m deep, with high marine biodiversity and strong currents that runs between Green Point and Mana Island. The fossil beds are the remnants of a podocarp forest in this swampy valley around 100,000 years ago.

Around 80,000 years ago, the climate and sea levels rose. The forest growing in the swampy valley was drowned and covered over with a layer marine sands and gravels. Evidence for this can be seen in the cliff at the south end of the Bay, which is composed of cemented marine sands and overlies the fossil stump beds. During this time, sea levels rose 2-4m higher than present.

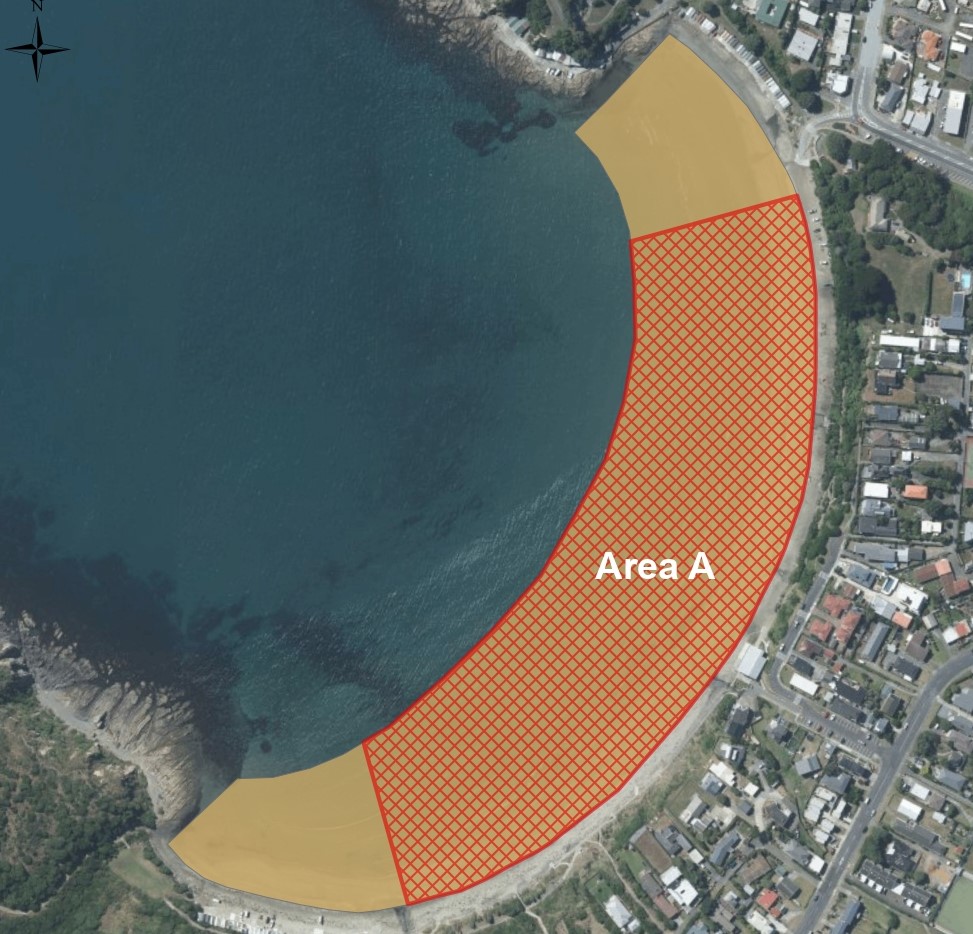

The stumps closest to the surface are intermittenly uncovered by storm erosion and are visible around the mid to low tide mark. The stumps have been largely unmodified apart from some abrasion and scuffing, where they get exposed to surf processes or have been driven on. However, it has been reported that in the past, some of the stumps on the beach were damaged by boat launching activities.

It is uncommon to see subfossil forests of this nature so easily and the Titahi Bay fossil forest showcases an excellent example of a paleo-environment for scientific and educational research. Understanding the historical climate is important for climate change research and future climate projections and this site provides a record of environmental conditions during the last Interglacial period that can help in this research.

The stumps are vulnerable to damage and disturbance from vehicles, boat launching, machinery, beach grooming and vandalism and there would be no way to remediate the damage if it occurred (Begg & Mazengarb, 1996; Campbell, 1996; Gibb, 2012; Mildenhall, 1993).

For more information about the Titahi Bay Fossil Forest, check out the GNS Science GeoTrip website.

Exposed fossil on the beach (Photo: Iain Dawe)

Exposed fossil on the beach (Photo: https://www.geotrips.org.nz/trip.html?id=32, J.Thomson, GNS)

References

Begg, J.G. & Mazengarb, C. (1996), Geology of the Wellington Area 1:50,000 Geological Map 22. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 128p + map.

Campbell, H.J. (1996), Titahi Bay fossil forest floor. Geological Society of New Zealand Newsletter, No. 110, 22-24.

Gibb, J.G. (2012), Local Relative Holocene Sea Level Changes for the Porirua Harbour Area, Greater Wellington Region. Report prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council, Coastal Management Consultancy, C.R. 2012/1, 16p.

Mildenhall, D.C. (1993), Last glaciation/postglacial pollen record for Porirua, near Wellington, New Zealand. Tuatara, 32, 22-27.